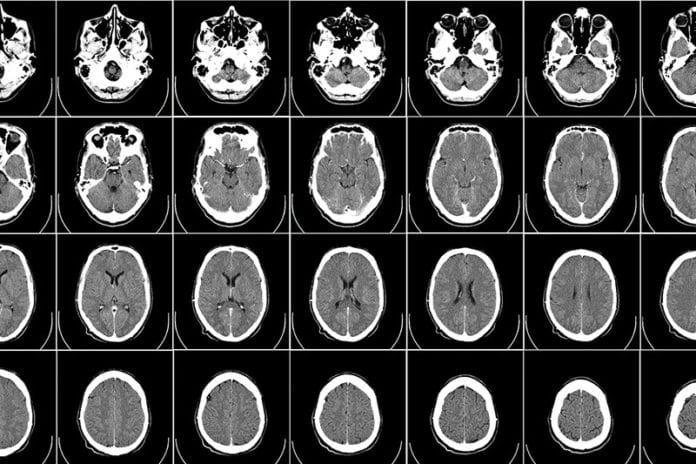

Primary brain tumors encompass a wide range of tumors depending on the cell type, the aggressiveness, and stage of tumor. Quickly and accurately characterizing the tumor is a critical aspect of treatment planning. It is a task currently reserved for trained radiologists, but in the future, computing, and in particular high-performance computing, will play a supportive role.

George Biros, professor of mechanical engineering and leader of the ICES Parallel Algorithms for Data Analysis and Simulation Group at The University of Texas at Austin, has worked for nearly a decade to create accurate and efficient computing algorithms that can characterize gliomas, the most common and aggressive type of primary brain tumor.

Biros and collaborators from the University of Pennsylvania, University of Houston, and University of Stuttgart, have created a new, fully automatic method that combines biophysical models of tumor growth with machine learning algorithms for the analysis of Magnetic Resonance (MR) imaging data of glioma patients. All the components of the new method were enabled by supercomputers at the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC).

Biros' team tested their new method in the Multimodal Brain Tumor Segmentation Challenge 2017 (BRaTS'17), an annual competition where research groups from around the world present methods and results for computer-aided identification and classification of brain tumors, as well as different types of cancerous regions, using pre-operative MR scans.

Their system scored in the top 25 percent in the challenge and were near the top for whole tumor segmentation.

"The competition is related to the characterization of abnormal tissue on patients who suffer from glioma tumors, the most prevalent form of primary brain tumor," Biros said. "Our goal is to take an image and delineate it automatically and identify different types of abnormal tissue - edema, enhancing tumor (areas with very aggressive tumors), and necrotic tissue. It's similar to taking a picture of one's family and doing facial recognition to identify each member, but here you do tissue recognition, and all this has to be done automatically."

TRAINING AND TESTING THE PREDICTION PIPELINE

For the challenge, Biros and his team of more than a dozen students and researchers, were provided in advance with 300 sets of brain images on which all teams calibrated their methods (what is called "training" in machine learning parlance).

In the final part of the challenge, groups were given data from 140 patients and had to identify the location of tumors and segment them into different tissue types over the course of just two days.

"In that 48-hour window, we needed all the processing power we could get," Biros explained.

The image processing, analysis and prediction pipeline that Biros and his team used has two main steps: a supervised machine learning step where the computer creates a probability map for the target classes ("whole tumor," "edema," "tumor core"); and a second step where they combine these probabilities with a biophysical model that represents how tumors grow in mathematical terms, which imposes limits on the analyses and helps find correlations.

TACC computing resources enabled Biros' team to use large-scale nearest neighbor classifiers (a machine learning method). For every voxel, or three-dimensional pixel, in a MR brain image, the system tries to find all the similar voxels in the brains it has already seen to determine if the area represents a tumor or a non-tumor.

With 1.5 million voxels per brain and 300 brains to assess, that means the computer must look at half billion voxels for every new voxel of the 140 unknown brains that it analyzes, deciding for each whether the voxel represents a tumor or healthy tissue.

"We used fast algorithms and approximations to make this possible, but we still needed supercomputers," Biros said.

Each of the several steps in the analysis pipeline used separate TACC computing systems. The nearest neighbor machine learning classification component simultaneously used 60 nodes (each consisting of 68 processors) on Stampede2, TACC's latest supercomputer and one of the most powerful systems in the world. (Biros was among the first researchers to gain access to the Stampede2 supercomputer in the spring and was able to test and tune his algorithm for the new processors there.) They used Lonestar 5 to run the biophysical models and Maverick to combine the segmentations.

Most teams had to limit the amount of training data they used or apply more simplified classifier algorithms on the whole training set, but priority access to TACC's ecosystem of supercomputers meant Biros' team could explore more complex methods.

"George came to us before the BRaTS Challenge and asked if they could get priority access to Stampede2, Lonestar5, and Maverick to ensure that their jobs got through in time to complete the challenge," said Bill Barth, TACC's Director of High Performance Computing. "We decided that just increasing their priority probably wouldn't cut it, so we decided to give them a reservation on each system to cover their needs for the 48 hours of the challenge."

As it turned out, Biros and his team were able to run their analysis pipeline on 140 brains in less than 4 hours and correctly characterized the testing data with nearly 90 percent accuracy, with is comparable to human radiologists.

Their method is fully automatic, Biros said, and needed only a small number of initial algorithmic parameters to assess the image data and classify tumors without any hands-on effort.

INTEGRATING DIVERSE RESEARCH

The team's scalable, biophysics-based image analysis system was the culmination of 10 years of research into a variety of computational problems, according to Biros.

"In our group and our collaborators' groups, we have multiple research threads on image analysis, scalable machine learning and numerical algorithms," he explained. "But this was the first time we put everything together for an application to make our method work for a really challenging problem. It's not easy, but it's very fulfilling."

The BRaTS competition thus represents a turning point in his research, Biros said.

"We have all the tools and basic ideas, now we polish it and see how we can improve it."

The image segmentation classifier is set to be deployed at the University of Pennsylvania by the end of the year in partnership with his collaborator, Christos Davatzikos, director of the Center for Biomedical Image Computing and Analytics and a professor of Radiology there. It won't be a substitute for radiologists and surgeons, but it will improve the reproducibility of assessments and potentially speed up diagnoses.

The methods that the team developed go beyond brain tumor identification. They are applicable to many problems in medicine as well as in physics, including semiconductor design and plasma dynamics.

Said Biros: "Having access to TACC supercomputers makes our life infinitely easier, makes us more productive and is a real advantage."